Sustainable nature

2021

collage and

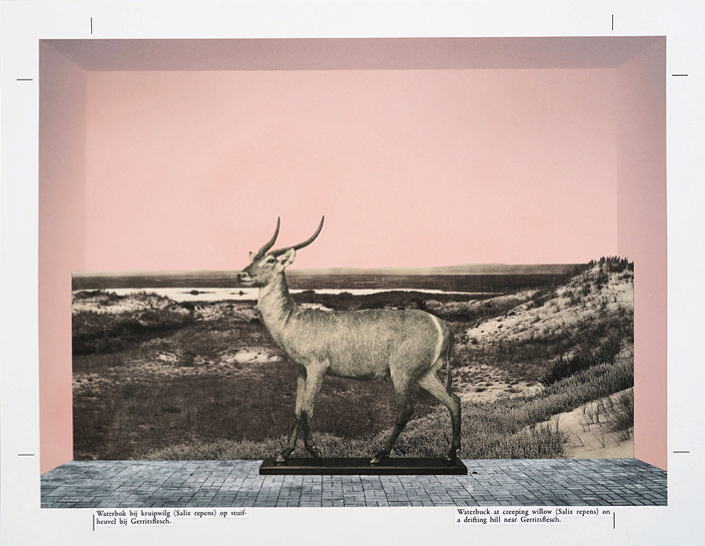

inkjet ink on

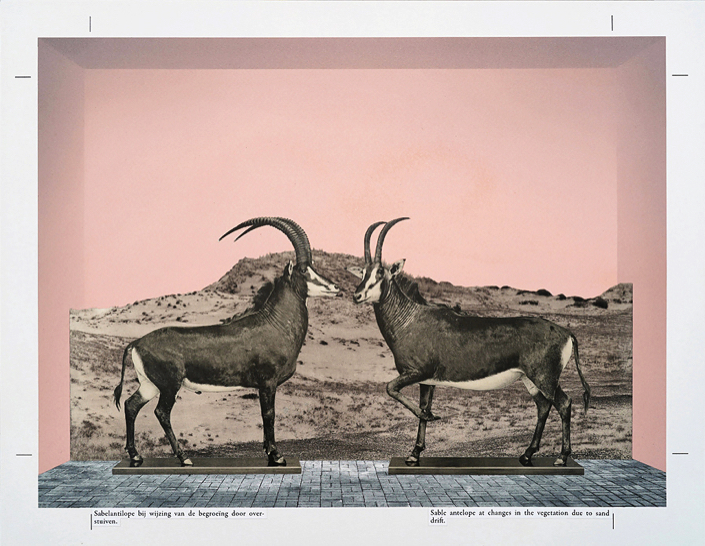

coloured paper

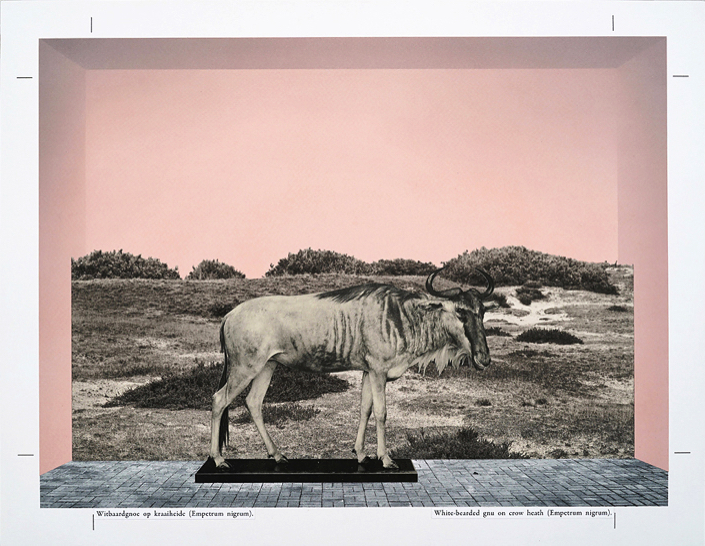

mounted on

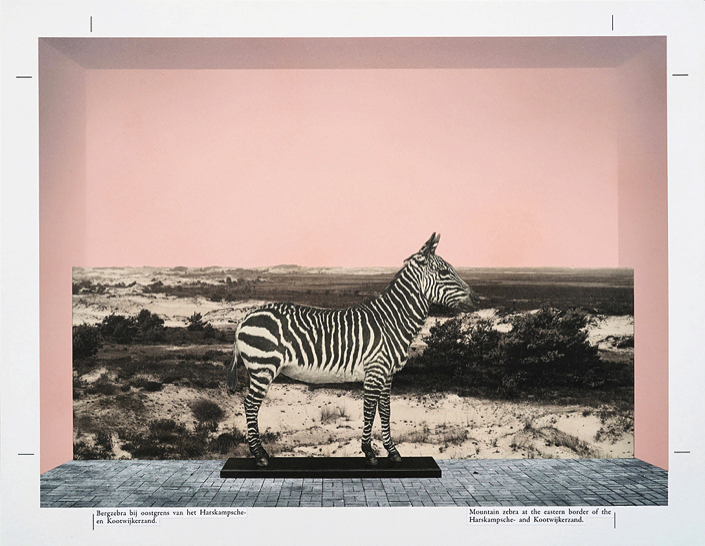

museum board

14 collages

(one work)

each

35 x 45 cm

3 - Waterbuck at creeping willow (Salix repens) on a drifting hill near Gerritsflesch.

4 - Mountain zebra at the eastern border of the Harskampsche- en Kootwijkerzand.

8 - Sable antelope at changes in the vegetation due to sand drift.

11 - White-bearded gnu on crown heath (Empetrum nigrum).

Luuk Wilmering

From the late 18th Century until the mid-20th Century, specimens were collected from nature and brought inside to be examined by scientists in university rooms and laboratories. Results from the hoarding craze of that time can still be found in natural history museums. Throughout the years, I've visited many such museums, in Bern, Frankfurt, Berlin, Aberdeen, London, Dublin, New York and Cairo. In several of them, I was also able to visit their depot, like in the Grande Galerie de l'Évolution, in Paris, the Natural History Museum Rotterdam and the Zoological Museum in St Petersburg. These depots contain enormous collections of dead animals. Storerooms filled with taxidermised mammals, cabinets full of birds and eggs, drawers full of insects, in bewildering amounts. What's the use of such numbers for the sake of science, you might ask? Couldn't it have been a few less?

One of those 'collectors' was the American biologist, sculptor, nature photographer and inventor Carl E. Akeley. As a taxidermist, he developed a new way of constructing museum displays, in which animals would be presented in their natural habitat. His method of reattaching an animal's skin to an exactly shaped copy of its body gave it a realistic result that had been previously unparalleled, and changed perceptions of taxidermy entirely. Akely is known for his contributions to many American museums.

Hunting for animals, to later show them in dioramas, was common practice for a long time. Many of these dead animals can still be viewed in museums like the Senckenberg Naturmuseum in Frankfurt, the Naturhistorisches Museum Bern and in many of the other museums I've visited. These dioramas are often marvellous, and the animals in them appear more sustainable than they would in nature itself, where they often decompose quickly after they die. Not in these museums, however: here, they are eternalised in tableau vivants.